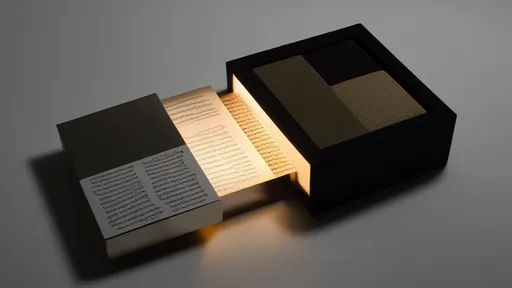

The world of poetry has long been confined to the visual and auditory realms—words printed on paper or spoken aloud. But what if poetry could be felt? This is the radical premise behind Tactile Poetry Blind Box: A Textural Experience of Material Language, an innovative project that reimagines verse as something to be touched, explored, and physically interacted with. By translating linguistic patterns into textured surfaces, this experiment blurs the line between literary art and sensory engagement.

Each blind box contains a poem rendered not in ink, but in carefully selected materials—rough burlap for harsh consonants, smooth silk for flowing vowels, raised Braille-like dots for rhythmic structure. The experience is deliberately opaque; participants don’t know which poem they’ll receive until they run their fingers across its topography. This element of chance mirrors the unpredictability of language itself, where meaning often emerges through unexpected combinations.

The project’s creators—a collective of poets, tactile designers, and neuroscientists—argue that touch has been unjustly excluded from literary consumption. "We read with our eyes, recite with our mouths, but rarely do we feel words in a literal sense," notes lead designer Elara Voss. Her team’s research suggests that texture can evoke emotional responses comparable to metaphor or alliteration. A jagged, abrasive surface might convey anger more viscerally than adjectives ever could, while undulating waves of velvet could mimic the cadence of love poetry.

Early participants describe uncanny moments of synesthesia—where tactile input spontaneously generates auditory or visual impressions. One reviewer wrote of "hearing whispers" when tracing a particularly intricate fiber arrangement, while another reported "seeing bursts of color" behind closed eyelids during exploration. These accounts hint at poetry’s primal power to bypass rational processing and speak directly to the senses.

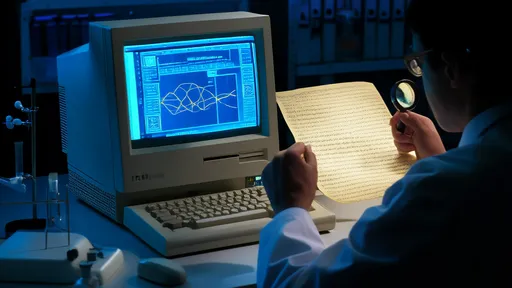

Critics initially dismissed the concept as a gimmick, but the blind boxes have gained a cult following among educators working with visually impaired students. Traditional Braille poetry, while vital, remains bound to linguistic transcription. These textural interpretations offer an alternative—not replacing words, but augmenting them with sensory dimensions that sighted readers often take for granted. At the Brooklyn School for the Blind, teachers report students debating the "shapes" of Emily Dickinson’s dashes or the "weight" of Langston Hughes’ syllables with unprecedented fervor.

The commercial release has sparked controversy in literary circles. Purists argue that divorcing poetry from its textual form erases authorial intent, while avant-garde champions hail it as the next evolution of concrete poetry. Sales figures suggest the public’s appetite for experiential literature is growing; the first print run sold out within hours, with boxes now trading at triple their original price on collector forums.

Perhaps most intriguing is the project’s accidental democratization of poetry interpretation. Without visual typography or vocal inflection to guide them, participants from different linguistic backgrounds arrive at strikingly similar emotional conclusions when handling the same piece. A Japanese architect and a Brazilian florist independently described one texture sequence as "the physical sensation of nostalgia"—despite neither knowing they were touching an adaptation of Rilke’s Autumn Day.

As museums begin acquiring these boxes for their permanent collections, questions arise about preservation. How does one conserve materials meant to be worn down by touch? The team’s solution—periodically replacing components while documenting each version’s gradual transformation—turns decay into part of the artistic statement. Like language itself, the poems evolve through use.

Future iterations may incorporate temperature-conductive alloys that shift with body heat or micro-encapsulated scents released by pressure. For now, these unassuming boxes—no larger than a paperback—contain multitudes. They challenge us to reconsider poetry not as an intellectual exercise, but as a full-body encounter with the raw material of human expression.

In an age of digital overload, the deliberate slowness of tactile reading feels revolutionary. There are no notifications, no hyperlinks—just fingers moving across surfaces, minds assembling meaning from friction and form. As one participant remarked: "It’s the first time I’ve ever needed to close my eyes to truly see a poem."

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025

By /Jul 23, 2025